الهجمات على التراث الثقافي، دروس من التاريخ

هيرمان بارزينغر

شهد التاريخ على امتداده تدميرًا مقصودًا للتراث الثقافي. وبينما تختلف دوافع ذلك، إلا أنه عادة ما يكون للعوامل الاقتصادية دور في ذلك الخليط من الأسباب، بينما كانت الدوافع السياسية هي الأبرز في الحقب القديمة. وفي الفترة الأخيرة، أصبحت الإبادة الجماعية الثقافية مرافقة للجرائم الوحشية في السياق الاستعماري الأوروبي، وتبدو شائعة كذلك في معظم الحالات التي جرت في القرن العشرين ومطلع القرن الحادي والعشرين عندما أصبحت الشعوب وهويتها الثقافية بمثابة أهداف رئيسية.

ملخص

يسبر هذا الفصل تاريخ التدمير المقصود للتراث الثقافي بدءًا من العصور القديمة وصولًا إلى يومنا هذا. ويُحلل الظروف والدوافع السياسية والدينية والاجتماعية والعرقية وغيرها التي تدفع نحو تدمير المقتنيات الثقافية وطمس التراث الثقافي. ومن بين الروابط ذات الأهمية الخاصة، تلك المتعلقة بجرائم الحرب والجرائم ضد الإنسانية وغيرها من الجرائم الوحشية التي يتم اقترافها بحق السكان المدنيين. تتم دراسة هذه الروابط عبر حالات من العصور القديمة وصولًا إلى حرب الأيقونات البيزنطية، وحرب الأيقونات إبان فترة الإصلاح البروتستانتي، والعصر الاستعماري الأوروبي، والثورتان الفرنسية والروسية، والحقبة النازية التي شهدت مستويات غير مسبوقة من الطمس الممنهج للثقافة والإنسانية. ومن بعدها، نسلّط الضوء على جرائم الخمير الحمر في كمبوديا والتطهير العرقي والثقافي في حروب البلقان. وأخيرًا، شهدنا على مستوى جديد من الضراوة في إبادة التراث الثقافي والإنسانية التي استغلتها ما تُسمى "الدولة الإسلامية في العراق والشام" لغايات دعائية أمام أنظار العالَم.

遭受摧残的文化遗产——以史为鉴

赫尔曼·帕辛格 (Hermann Parzinger)

从古至今,文化遗产时常遭到蓄意摧毁。尽管动机各不相同,但其中往往不乏经济因素,而在古代,政治动机则占据首位。近年来在各个欧洲殖民国家,文化灭绝往往伴随着残酷暴行,在 20 世纪及 21 世纪初尤为常见,袭击的主要目标为人民及其文化身份。

摘要

本章探究了从古至今蓄意摧毁文化遗产行为的历史,并分析了致使文化产品与文化遗产惨遭摧毁的政治、宗教、社会、种族及其它状况与动因。尤其值得注意的是其与残害平民的战争犯罪、危害人类罪及其它暴行之间的关联。作者引用从古代至拜占庭时期的圣像破坏运动、新教宗教改革、欧洲殖民时期、法国大革命、俄国革命,以及将系统性消灭文化与人性发挥到极致的纳粹时期的各种案例,对这样的关联进行了探究。之后,作者着重介绍了柬埔寨红色高棉组织的罪行以及巴尔干战争中的种族与文化清洗运动。最后,作者揭露了伊朗与叙利亚所谓的伊斯兰教国以布教为目的在全球人民的注视下摧毁文化遗产及人民的极恶行径。

Intentional destruction of cultural heritage has occurred throughout history. While motivations may have differed, economic factors have usually been part of the mix, with political motives paramount in antiquity. More recently, cultural genocide has accompanied mass atrocities in European colonial contexts and also seems common in most cases of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, when people and their cultural identity have become key targets.

Abstract

This chapter explores the history of the intentional destruction of cultural heritage from ancient times to the present. It analyzes the political, religious, social, ethnic, and other conditions and motivations that feed the obliteration of cultural artifacts and cultural heritage. Of particular interest are the links to war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other atrocities perpetrated against civilian populations. These connections are explored in cases from antiquity to the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy, the iconoclasm of the Protestant Reformation, the European colonial age, the French and Russian Revolutions, and the Nazi era, when the systematized obliteration of culture and humanity reached new levels. Next, the crimes of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and the ethnic and cultural cleansings of the Balkan Wars are highlighted. Finally, another dimension of ruthlessness is reached with the annihilation of cultural heritage and humanity that the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria exploited for propaganda purposes before the eyes of a global audience.

Le patrimoine culturel assiégé, les enseignements tirés de l’histoire

Hermann Parzinger

La destruction intentionnelle du patrimoine culturel s’est produite tout au long de l’histoire. Si les motivations ont pu différer, les facteurs économiques ont habituellement fait partie de l’ensemble, les motifs politiques ayant été prédominants dans l’Antiquité. Plus récemment, le génocide culturel s’est accompagné d’atrocités de masse dans des contextes coloniaux européens, et il semble également courant dans la plupart des cas au vingtième comme au début du vingt-et-unième siècle, alors que les peuples et leur identité culturelle sont devenus des cibles primordiales.

Résumé

Ce chapitre explore l’histoire de la destruction intentionnelle du patrimoine culturel des temps anciens jusqu’à l’époque présente. Il analyse les motivations politiques, religieuses, sociales, ethniques, ainsi que les autres conditions et motivations qui ont contribué à l’oblitération d’artéfacts culturels et d’une partie du patrimoine culturel. Les liens avec les crimes de guerre, les crimes contre l’humanité, et les autres atrocités perpétrées contre les populations civiles présentent un intérêt particulier. Ces connexions font l’objet d’une étude dans des situations allant de l’Antiquité jusqu’à la querelle iconoclaste byzantine, l’iconoclasme de la Réforme protestante, la période coloniale européenne, les révolutions française et russe, et l’époque Nazie, lorsque l’oblitération systématique de la culture et de l’humanité a atteint des niveaux sans précédent. Puis, les crimes des Khmers rouges au Cambodge, ainsi que le nettoyage ethnique et culturel des guerres des Balkans, sont mis en exergue. Enfin, une autre dimension de cruauté est atteinte avec l’annihilation d’une partie du patrimoine culturel et de personnes que le soi-disant État islamique en Irak et en Syrie a exploitée à des fins de propagande sous les yeux d’une audience mondiale.

Культурное наследие под ударом. Уроки истории.

Герман Парцингер

Культурное наследие подвергалось намеренному уничтожению на протяжении истории человечества. Хотя причины этого могли быть разными, в большинстве случаев экономические факторы играли свою роль, в то время как в древности первостепенное значение имели политические цели. Позже, в контексте европейского колониализма, культурный геноцид сопровождал массовые злодеяния. В двадцатом веке, как и в начале двадцать первого, когда люди и их культурная принадлежность стали основной мишенью насилия, культурный геноцид представляется частым явлением.

Краткое содержание

В этой главе рассматривается история намеренного уничтожения культурного наследия с древнейших времен до современности. В ней анализируются политические, религиозные, социальные, этнические и другие условия и мотивы, которые приводят к разрушению культурных артефактов и культурного наследия. Особое внимание уделено связям между военными преступлениями, преступлениями против человечества и другими злодеяниями против гражданского населения. Связь между этими феноменами исследуется на примерах Античности, истории иконоборчества в Византии и во времена Протестантской Реформации, периода европейского колониализма, Великой французской и русской революций и нацизма, при котором систематическое уничтожение культуры и человеческих жизней достигло нового уровня. Кроме того, освещены преступления Красных кхмеров в Камбодже, а также этнические и культурные чистки во время войны на Балканах. Наконец, беспрецедентная жестокость была проявлена в актах уничтожения культурного наследия и мирного населения, которые в так называемом Исламском государстве в Ираке и Сирии были использованы для пропагандистских целей на глазах у мировой общественности.

El patrimonio cultural amenazado: aprender de la historia

Hermann Parzinger

La destrucción intencional del patrimonio cultural ha ocurrido a lo largo de la historia. Aunque las motivaciones pueden haber variado, los factores económicos a menudo han desempeñado cierto papel y los motivos políticos fueron fundamentales en la Antigüedad. Más recientemente, el genocidio cultural ha acompañado a las atrocidades en masa ocurridas en los contextos coloniales europeos y parece también común en la mayoría de los casos del siglo XX y principios del siglo XXI, cuando las personas y su identidad cultural se han convertido en blancos clave.

Resumen

Este capítulo explora la historia de la destrucción intencional del patrimonio cultural desde la Antigüedad hasta el presente. Analiza las condiciones y motivaciones políticas, religiosas, sociales y étnicas, entre otras, que impulsan la erradicación de los artefactos culturales y el patrimonio cultural. Resultan particularmente interesantes las conexiones con los crímenes de guerra, los crímenes de lesa humanidad y otras atrocidades perpetradas contra poblaciones civiles. Estas conexiones se exploran en casos que abarcan desde la Antigüedad a la controversia iconoclasta bizantina, la iconoclasia de la Reforma protestante, la era colonial europea, las revoluciones francesa y rusa, y la era nazi, en la que la destrucción sistematizada de la cultura y la humanidad alcanzó nuevos niveles. A continuación, se ponen de relieve los crímenes de los Jemeres Rojos en Camboya y las limpiezas étnicas y culturales de las guerras de los Balcanes. Por último, se alcanza un nuevo nivel de crueldad con la aniquilación del patrimonio cultural y la humanidad que el llamado Estado Islámico en Irak y Siria ha aprovechado para hacer propaganda ante la mirada del público mundial.

The history of the intentional destruction of cultural heritage is long and diverse,1 with motivations similarly varied. Ideologically or politically motivated iconoclasm seeks to destroy symbols and representational signs that characterize a past that has been vanquished, or a deposed system to purge its memory. Religious iconoclasm is fed by the hatred of images of another religion, as well as the fight against idolatry and false gods in the service of the true faith. Economically motivated cultural destruction is characterized by the pillage and plunder of culturally significant sites or monuments for financial gain, which at times may give rise to shadow economies. It may not always be possible to clearly differentiate between the various reasons driving the destruction of cultural heritage, but they are closely intertwined. Cultural destruction also often goes hand in hand with human rights violations and other atrocities; particularly when the latter involve ethnic cleansing and genocide. These interconnections will be explored in detail throughout this essay.

The Beginnings: Cultural Destruction during Antiquity

Ancient sources support the notion that a plurality of motivations drive the destruction of cultural heritage. Craving recognition, Herostratus set ablaze the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, in Asia Minor, in 365 BCE. Seeking revenge, Alexander the Great destroyed the Persian capital of Persepolis in 330 BCE, Rome sacked the Greek city of Corinth in 146 BCE, and both were surprising in their ruthlessness and made little sense militarily. And for political reasons, Carthage was razed on the orders of Roman general Scipio (in the same year as Corinth) to vanquish one of Rome’s most important contemporary competitors.2 The civilian populations were also gravely affected by such destruction, as it was commonly accompanied by massacres and enslavement.

Pillage and plunder of the spoils of a defeated city by the victorious power was commonplace in ancient times and in later eras was deemed the right of the victor, while the defeated population was for the most part barred from any rights and protection. Anything valuable and somewhat usable was stolen. However, at stake in these attacks was not any targeted destruction of works of art and cultural artifacts in the sense of an iconoclastic campaign, driven by the social belief in the importance of the destruction of icons and other images or monuments for political or religious reasons. In fact, such artifacts were often subject to political appropriation and rededication: by exhibiting them as trophies of victory in the public domain, military victories over other peoples could be permanently memorialized and claims to domination effectively visualized.3 The destruction of cultural heritage during ancient times was thereby in most cases politically motivated.

Cultural heritage destruction coupled with atrocities against populations are also known from the time of Ancient Mesopotamia. Thus, after the demise of the Assyrian Empire around 600 BCE an intense hatred was unleashed on cities like Assur and Nineveh, leaving behind clearly visible traces of destruction of works of art: e.g., sarcophagi of the Assyrian rulers were demolished and their faces systematically purged from the palace reliefs because the vanquished were to be denied the possibility of immortalizing their glorious feats for posterity. The Assyrians had previously reacted similarly in obliterating particular rulers and dynasties from collective memory by destroying their sculpted images, a familiar practice throughout the ancient world.4

After the rise of Christianity in late antiquity, particularly the eastern parts of the Roman Empire saw clashes between the followers of Christianity and practitioners of pagan cults.5 The forces driving these hostilities also strove for political and economic power. On the Christian side, the focus was not solely on the obliteration of pagan sanctuaries and their conversion to churches; rather, a central concern was also the seizure of each temple’s wealth in gold, silver, precious stones, and other treasures.

The destruction and looting of a temple known as the Serapeum of Alexandria in 392 CE was the climax of antipagan violence and seizures. Serapis was revered equally by the Egyptian and Greek inhabitants of the city—in fact, the Serapeum was deemed Alexandria’s most significant sanctuary. The violent suppression of all pagan cults that was orchestrated by the Christian bishop Theophilos resulted in extreme polarization of the population of the early Christian Roman Empire. He provoked bloody clashes, then accused the pagans of rioting. After the pagans had barricaded themselves inside the temple, the imperial order came down authorizing its destruction and the future suppression of any exercise of pagan cults. The Serapeum of Alexandria and other temples were leveled, a devastation that went hand in hand with widespread pillage and plunder. The central idol of the Serapeum of Alexandria was hacked into pieces and scattered for public display at different locations within the city, only to be subsequently burned at the amphitheater. A more horrific desecration is scarcely conceivable.6

Ideological-religious conflicts in late antiquity resulted in enormous destruction of cultural heritage. Aside from securing the victory of Christianity, another concern was the redistribution of resources that could confer wealth, prestige, and power to the holder. Religious contradictions were not the driving force, but more often merely a pretext. Particularly in the Eastern Roman Empire, during late antiquity the state was more often the driven, and not the driving force, in these conflicts. The late Roman administration often had few instruments at its disposal to counter the organizational capability, military prowess, and mobilization potential of the Byzantine church. Contemporary sources widely disregard the consequences for the population, yet the devastation of pagan sanctuaries, besides being provoked by economic motives, was associated with massacres among the members of their practitioner communities, though the latter were not the actual target.

Religion and Power: From the Iconoclastic Controversy in Byzantium to the Bildersturm of the Protestant Reformation

The period between the eighth and sixteenth centuries saw multiple iconoclastic controversies.7 Unlike the cultural destruction of late antiquity, a theological conflict on the permissibility of “iconic” depictions in religious contexts stood at the center of this debate. Particularly the question of if, and if so to what extent, it was permissible for believers to create and worship human-like images of God, icons of Jesus, and representations of the saints.

Between 730 and 841, Christian monasteries in the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire safeguarded cultural images and relics that had ascribed to them the most varied curative powers. Yet in order for popular interaction with these images and for their curative powers to emerge, the monastery was owed payment. Such measures helped monasteries strengthen their economic power as whole town populations became increasingly interdependent with monasteries, which were built as regular fortresses and enjoyed tax advantages. At the end of the seventh century, one-third of imperial lands were in the hands of churches and monasteries, and an ever more impoverished state stood opposite an increasingly affluent Byzantine church.8

By the eighth century, a gradual shift in the power structure had advanced to such a perilous degree that the monasteries found themselves gravely challenged. As pagan temples had been looted during late antiquity for their accumulated treasures, the Byzantine state appropriated the riches of the Christian monasteries during the eighth and ninth centuries. This political and economic struggle needed an ideological-theological foundation, a realization that resulted in the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy. From its very beginning, this debate had political implications and was ordered from the top, by the state. Indiscriminate, unbridled destruction was to be avoided at all cost, and the population was for the most part not involved.

Moving westward, the Central European Hussite Wars of the early fifteenth century were different. The Bohemian preacher Jan Hus revived criticism of idolatry and challenged wealth, worldly passions for grandeur, moral decay, the Church’s trade in indulgences, and the supreme authority of the pope in questions of faith. In 1415, at the Council of Constance, despite assurances of safe conduct, Hus was accused of heresy and convicted and burned along with his writings. His reformist critical teachings subsequently morphed into a revolutionary mass movement in Bohemia, culminating in the Hussite Wars of 1419–34.9

Known in German as the Bildersturm (picture storm), the iconoclasm of the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation was similar. For Martin Luther, the fight against idolatry was secondary, with his rage directed at other grievances against the Church, particularly the sale of indulgences by which it accumulated tremendous assets, including art treasures. Although Luther was not a radical iconoclast, his teachings had lasting consequences for the production of art in territories under Protestant rule: the fabrication of elaborate altars, tableaux, and sculptures, as well as luxurious chasubles or liturgical utensils of precious metals, plummeted.10

In contrast, the Swiss reformers Ulrich Zwingli and Johannes Calvin demonstrated a visibly more iconoclastic attitude. They rejected any representation of God and ordered the removal of all such images from the churches, arguing they promoted idolatry and carnal desire. The systematic removal of representational images throughout Europe during the Reformation was typically organized by government authorities in efforts to avoid spontaneous acts of violence.11 A significant number of works of art, images, and sculptures was sold for profit, resulting in an enormous influx of wealth to state coffers.12 Still, again and again, radicalized masses engaged in unbridled orgies of destruction during which images were damaged, mutilated, and “executed” or derided in mock trials.13 The loss of works of art was enormous, far greater than the violence enacted upon the population, although violence also increased, climaxing in the Thirty Years’ War in the seventeenth century, when one-third of the population of Central Europe is thought to have perished.

Revolution and Colonization: The Long Nineteenth Century

The period between the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789 and the breakdown of the old European order after World War I is referred to as the “long nineteenth century.”14 The revolution was a turning point in the history of the destruction of cultural heritage.15 The iconoclasm of the revolutionaries was no longer religiously motivated, but was propelled by a secular cultural ideology. After the storming of the Bastille at the start of the French Revolution, the overriding objective of the new government was overcoming the political and social conditions of the ancien régime. Countless representatives of the fallen system fled abroad or ended up on the guillotine, and the works of art of that period were seen as symbolic of a hated despotism that had to be eliminated. In 1791, iconoclasm was legalized and elevated to a political program. During the next few years, destruction of cultural heritage went hand in hand with politically and socially motivated executions and persecutions, one a byproduct of the other without a direct causal link.

Palaces were looted and sprawling landed properties owned by the Church and the aristocracy were nationalized, with the intent of mitigating the chronic financial shortages of the revolutionary state.16 Tableaux and sculptures, illuminated manuscripts, luxurious furniture, and decorative arts, but also liturgical items such as reliquaries and monstrances of precious metal, fell into the hands of the revolutionaries, who melted them down or sold them. Even the mausoleums and tombs of the French kings, such as those in Saint Denis, a northern suburb of Paris, were looted and devastated. Bishop Henri Grégoire denounced this unrestrained destructive frenzy driven by blind rage, and coined the term “vandalism” to describe it.17

Parallel to the growing resistance to the revolutionary destructive madness, a basic rethinking introduced a new phase in French cultural policy. This new approach was based on the understanding that it does not make sense to nationalize works of art while simultaneously destroying or selling them abroad. Rather, proponents of the new view believed that the nationalization of cultural wealth came with the obligation to preserve and maintain it. This impulse was the beginning of a new understanding of the concept of cultural heritage (French patrimoine).18 And administrative mechanisms ultimately channeled and institutionalized the iconoclasm of the revolution, resulting in a growing respect for works of art and the birth of the modern museum, viewed also as an institution of learning, which found a home in the Louvre.19 After the politically motivated iconoclasm of the French Revolution there emerged a new appreciation for art based on the understanding that it can make a crucial contribution to higher learning and the self-realization of humankind.

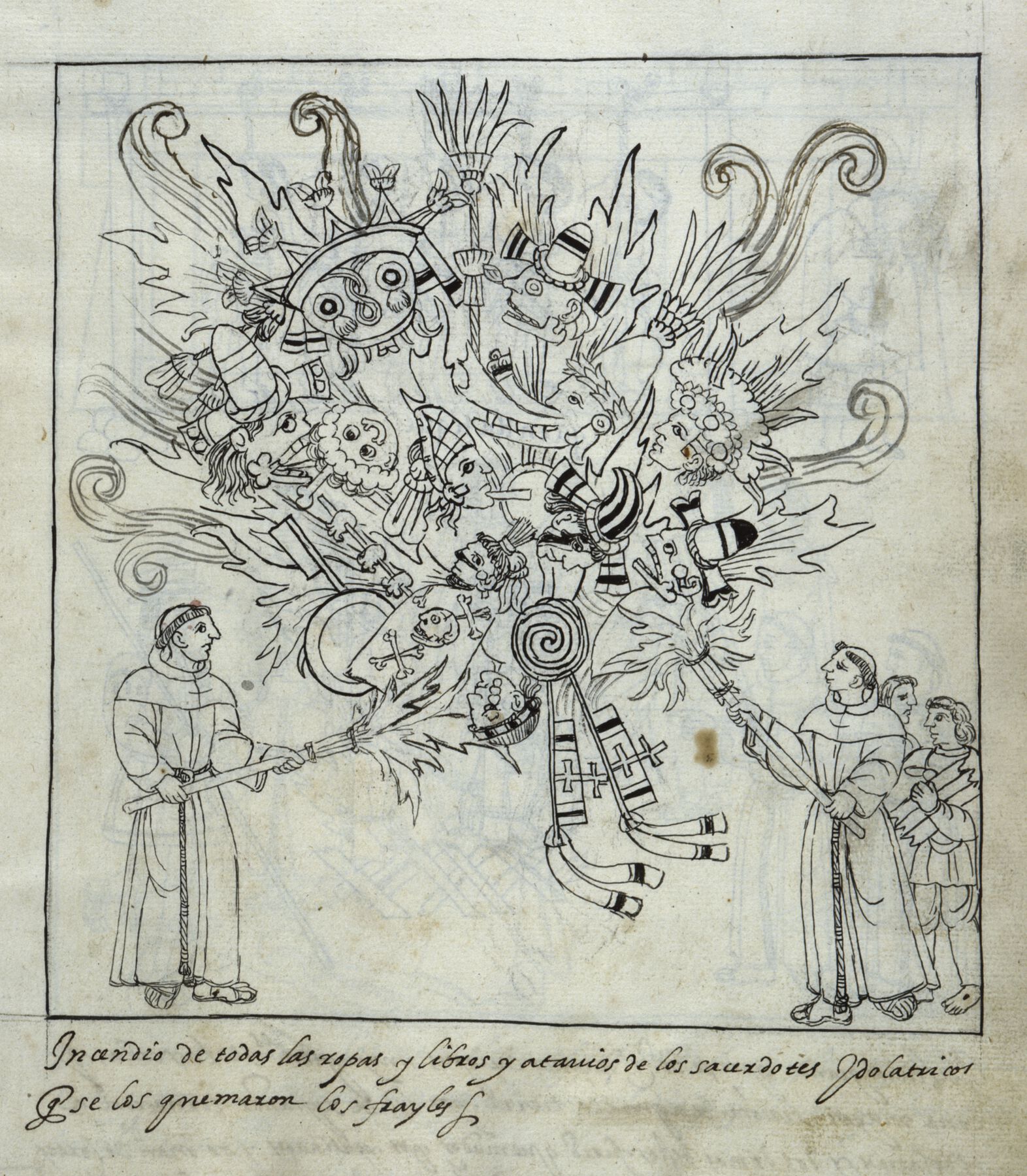

The nineteenth century was also the climax of the conquest of the world by European colonial powers. Lasting half a millennium, this global subjugation and exploitation resulted in the destruction of cultural heritage of staggering proportions. Destruction was always accompanied by atrocities against Indigenous populations, of a severity that, at the time, would have been unfathomable within Europe itself. This occurred as early as the sixteenth century, during the colonial conquest of Central and South America by the Spanish and Portuguese. Two large and growing empires—that of the Aztecs in modern Mexico and the Incas in the Andes region in South America—were completely obliterated.20 The devastation ranged from the destruction of monumental buildings and the looting of shrines to the incineration of written traditions or codes (fig. 3.1). Not only did this result in an immense loss of knowledge, it was the start of cultural as well as physical genocide.

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1From the middle of the nineteenth century China also found itself in the crosshairs of European colonial powers. At the end of the Second Opium War in 1860, British and French troops seized the capital of Beijing and attacked the imperial Old Summer Palace in Yuanmingyuan—the Chinese version of the Palace of Versailles in Paris—northwest of the city. Marauding soldiers went on an unimaginable rampage, burning down the entire palace district and looting thousands of important works of art and cultural artifacts of gold, silver, jade, ivory, and so on.21 The estimated tally stands at over a million items stolen and sold to museums around the world.

In 1900, what became known as the Boxer Rebellion broke out in opposition to increasing European influence in China but was crushed by an international military force the following year. The expedition turned into a merciless retaliatory campaign of revenge against the Chinese people and culture in which the invaders were responsible for appalling atrocities, destruction, pillage, and plunder. Many palace and temple installations inside and around Beijing were devastated and the palace complex known as the Forbidden City was desecrated and looted. Hundreds of thousands of art treasures and artifacts were destroyed or stolen, accompanied by executions and massacres.22 These events are burned into the collective memory of the Chinese people.

Around the same time, the British conducted a punitive expedition against Benin in southwest Nigeria, one of the most flourishing kingdoms in the sub-Saharan Africa of the late nineteenth century. Its metal foundry works, including commemorative heads and relief plates of bronze and brass, as well as ivory carvings, were of particularly excellent quality. After the British conquered Benin’s capital in 1897, thousands of works of art from the palace districts were brought to London, and from there they were scattered around half the globe.23

While the historical context of each of these examples of cultural destruction is distinct, they nonetheless share the merciless brutality by which entire civilizations were debased, robbed, and sometimes annihilated. Yet the conflicts in China and Benin occurred during the period when the 1899 Hague Convention (II) with Respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land was being drafted.24 This expressly prohibited the looting and destruction of historically, culturally, and religiously significant locales and monuments. However, neither the Kingdom of Benin nor the Chinese Empire were signatories and so these rules were not applied to them. Moreover, outside Europe, plunder and attacks against civilian populations were considered legitimate during colonial wars. In his notorious “Hun Speech” Kaiser Wilhelm II expressly instructed the German East Asia squadron to be ruthless.25 This had to have been understood as an invitation to commit atrocities against the civilian population.

Nevertheless, the targeted destruction of works of art and artifacts played little role in World War I, the first industrially fought mass war resulting in millions of deaths. Among the few exceptions were the atrocities committed by German troops against a civilian population at the very beginning of the war in the Belgian city of Leuven. Its historical downtown, lined with important sacral and civic buildings from the late Middle Ages and Early Modern period, was looted and burned to the ground. The destruction of the city’s famous university library also resulted in an enormous loss of cultural artifacts. These events were a public relations disaster for the Germans, as shocked international observers spoke of the “holocaust of Leuven.” To make matters worse, Leuven was not an isolated incident: other Belgian cities with important historical centers were destroyed and looted during the first months of the war, a clear breach of the 1899 Hague Convention.26 It has been suggested that anti-Catholic resentment by the Prussian military, which was indebted to the Protestant confession, was instrumental in the decision to destroy the spiritual centers of Belgian Catholicism, robbing the population of its cultural identity.27 But these territories were slated to be incorporated into the German Reich after the end of the war, so this must remain speculative.

Radical Ideologies and Totalitarian Systems: The Catastrophes of the Twentieth Century

The breakdown of the old European order as a consequence of World War I, the “seminal catastrophe” of the twentieth century, fundamentally changed the world’s political landscape. The old German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires collapsed or were broken up into many new independent states. Territorial losses and newly drawn borders sowed discontent and ultimately destabilized an entire continent. This development paved the way for radical ideologies, such Bolshevism, National Socialism, Maoism, and that of the Red Khmer, all of whose propaganda of the utopian society had consequences for views on art and culture.

In Eastern Europe the war brought the demise of the Russian Empire and its replacement by the Soviet Union. Similar to the aftermath of the storming of the Bastille, the change was accompanied by looting and the destruction of monuments representing the old system.28 Revolution, civil war, and purges meant death for millions of Russians during the transition and in later years. Nonetheless, unlike the activists of the French Revolution, the new Bolshevik government in Russia was not interested in a targeted iconoclastic strategy. Even though monuments of the czars and any symbols and emblems directly linked to them were removed and their former owners expelled or executed, following an initial period of looting and vandalism there was a rather immediate impulse to protect and preserve cultural heritage and the imperial palaces were quickly placed under government supervision and repurposed as museums, declared the property of the people.29

The Bolsheviks gradually confiscated cultural artifacts and other valuables from palaces, manor houses, museums, and churches. But art was preserved, first and foremost, because of its monetary value, and so art was treated as a commodity. Necessitated by the never-ending financial difficulties of the young Soviet government, especially to fund rearmament and the repair of a dilapidated infrastructure, the most valuable incunabulae and manuscripts, as well as thousands of works of art, including master pieces from Russian museums, were sold abroad for hard currency. The hub for this sell-off of Russian cultural heritage was galleries in Berlin. Only when Hitler and the National Socialist Party came to power in Germany did this trafficking in Russian art end.30

Immediately after the Nazis’ Machtergreifung or “seizure of power” on 30 January 1933, the German government began a frontal assault on the arts and representatives of the arts, which was all the more destructive because, aside from its politico-ideological underpinnings, it was also characterized by a strong racial component.31 The book burnings of 1933 and the traveling propaganda exhibition “Degenerate Art” (Entartete Kunst) that began in 1937, were among the more prominent milestones on the path to discrediting and obliterating art and culture, along with their makers.32

The Law on Confiscation of Products of Degenerate Art of 1938 finally created a legal footing for the destruction of modern art. During the following few years, some twenty thousand works by about 1,400 artists were confiscated from over a hundred German museums.33 Hermann Göring, the second most powerful figure in the Third Reich until the later war years, was purportedly the first to float the idea of economic exploitation of this art. Commissioning transactions through selected art dealers, including Hildebrand Gurlitt, a systematic international sale of the confiscated “degenerate” art was organized via Swiss galleries in efforts to secure urgently needed hard currency for the Third Reich in support of the preparation and execution of its planned war of aggression.34

With the systematic extermination of Jewish life and culture as a core goal of the Nazis, discrimination, disenfranchisement, and looting started immediately after they took control of the government in 1933 (fig. 3.2). Major art collections owned by Jews, for example, were seized and placed in public museums, libraries, and archives.35 Remedying this injustice has become a special moral obligation the world over, leading to the search and restitution for illegally confiscated cultural artifacts and art looted by the Nazis also during World War II, based on the Washington Principles. The Nazi genocide against the Jewish population of Europe was also a cultural genocide, with all visible signs of Jewish culture obliterated.

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2Plunder, persecution, and oppression were also routine in the countries that the German army occupied during the war. The systematic looting of art and cultural artifacts reached staggering proportions, with Eastern Europe treated with particular cruelty. In their crazed fantasies of a large Germanic empire and of Lebensraum or “living space” in the east, the Nazis planned, in addition to the Holocaust, the mass murder of the Slavic and other non-Jewish populations of Poland and the Soviet Union. This was coupled with cultural genocide: all works of art and cultural artifacts that aroused the Nazis’ fancy were looted and transported to Germany, with the rest systematically destroyed.36 Museums, libraries, and archives, as well as palaces, mansions, and churches, in fact entire historical parts of towns of the highest cultural value, were obliterated. It was an iconoclasm of genocidal proportions, intended to rob human beings of their cultural identity.

From its early days, the intentional destruction of cultural heritage also played a crucial role in Mao Zedong’s communist movement in China. Already during the 1920s and 1930s the communists looted and demolished temples and ritual representational images as remnants of a feudal Chinese past. In 1966, under the People’s Republic, Mao generated the Cultural Revolution, which lasted until his death in 1976 and triggered a far greater wave of cultural destruction. Red Guards paramilitary revolutionary groups set their crosshairs on countless temples, shrines, cult images, and ritual objects, as well as porcelain, paintings, books, and manuscripts, in a campaign that sought to radicalize the entire nation and propagate Maoism as a religion.37 Artists whose works were declared “degenerate” were persecuted. The losses to Chinese cultural heritage were enormous. Yet works of art and artifacts were not only destroyed but also widely sold abroad—again, economic motivations played an important role.

The suppression of Tibetan culture in southwestern China has also been devastating. Tibet had declared independence in 1911, but Mao forcibly reincorporated it into the Chinese state shortly after the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. The war against Tibetan culture, which has centrally embraced Buddhism for perhaps fifteen hundred years, was executed ruthlessly and without consideration. For example, of over six thousand Buddhist temples and monasteries in Tibet before 1949, only thirteen still existed by the end of the Cultural Revolution.38

In Cambodia in 1975, a reign of terror began as the Khmer Rouge, a Maoist nationalist guerrilla movement, came to power under Pol Pot. Enamored with a preindustrial form of communism, they glorified agricultural life and deported a large segment of the urban population to the countryside. The land became a huge work and prison camp, with millions of people ending their lives in the “killing fields” of Cambodia, acts constituting crimes against humanity and arguably genocide. The wealthy and educated elite were exterminated, books were burned, universities closed down, and dance and music forbidden. The exercise of religion was also forbidden, and most of the country’s Buddhist temples and shrines were destroyed, along with churches and mosques. Works of art were demolished and incinerated to eliminate the prior cultural identity of the Cambodian people. In addition, there was systematic looting of historical sites and the sale and resale of valuable objects abroad:39 one aspect of this was the orchestration of the destruction of cultural heritage by promoting illegal excavations and organized trafficking in antiques—the first time this form of cultural destruction is known.

Ethnic and Religious Conflicts: The Crises of the Present

Throughout the last few decades, destruction of cultural heritage has often been encountered in the context of ethnic conflict. In the case of the wars in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the cultural heritage destruction was not random or unintentional—collateral damage in the course of military strife—but systematic and targeted. Serbs and Croats targeted mosques for bombing (fig. 3.3), Croats and Bosnians did the same to churches, and Serbs and Bosnians to Catholic places of worship—the sacral architecture of the enemy ethnic group was a preferred target. While the destruction of the symbolic Muslim bridge of Mostar awakened the international community, the Catholic episcopal palace, including its library, and the largest Catholic churches in the region were also severely damaged.40 The war was fought on parallel tracks—against the people and their culture and heritage—with particular ruthlessness. The intent was to thus make ethnic cleansing campaigns irreversible.

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3Serbs and Albanians also adhered to this strategy during the 1998–99 Kosovo War. Again, mosques and churches were in the crosshairs. Countless Orthodox churches and monasteries were destroyed, as were the majority of the mosques.41 The cultural and particularly the architectural heritage of the region became a symbolic battlefield.

Similar developments have occurred in the Middle East, where a devastating iconoclasm by Islamist extremists called attention to itself at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Yet the Qur’an does not unambiguously call for a ban on images. The early Islamic art of the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750) and even that of the succeeding Abbasids (750–1258) was replete with representational images that afterward survived in Islamic illumination.42 In contrast, the early Islamic Hadith literature, the collected sayings of Muhammed, contains critical statements regarding images; since then, the issue of whether representational images of a human likeness are permitted has been raised intermittently.

The beginnings of the militant Islamic attitude toward images is closely tied to the Sunni Wahhabi movement originating in the Arabian Peninsula in the eighteenth century, which subscribed to the verbatim implementation of all the early Islamic rules.43 The Wahhabis insist that any representation of Allah, any prayer directed at an image, or the veneration of a picture of a saint constitute blasphemy. In 1802, the Wahhabis conquered Kerbela in Iraq—one of the most important destinations for Shi’ite pilgrimage—where they destroyed and looted the Imam Husain shrine, killing thousands of Shi’ite faithful. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Wahhabi extremists intermittently destroyed holy sites in Mecca and Medina.44

In the early twenty-first century, the iconoclasm of the Islamists finally alerted the world to their cause when the Taliban demolished the colossal Buddha statues in Bamiyan, Afghanistan.45 This barbaric act was documented on film and reported worldwide, making it an act of performative iconoclasm before a global audience. The destruction of the statues was also an attack on a hegemonic conception of Western thought and on what the West understood as cultural heritage. Of course the cultural heritage of Afghanistan has been pillaged and plundered ever since the Soviet invasion in 1979: the Taliban utilized existing structures for unlawful illicit excavations and sold substantial parts of the country’s cultural heritage worldwide.46

Another recent example of cultural destruction motivated by fundamentalist thinking is found in Mali. In 2012, Islamist militias including Ansar Dine attempted to set up an independent Islamic state in the north of the country. When they conquered Timbuktu, one of the most significant cultural and intellectual centers of northern Africa, they destroyed most of the mausoleums that had declared been World Heritage Sites by the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). They also devastated many Sufi shrines and damaged mosques. A spokesperson for Ansar Dine put a shocked global public on notice that anything considered by sources outside Mali as constituting “world heritage” would be destroyed.47 It is a miracle that three hundred thousand volumes of the most valuable manuscripts and prints from the twelfth to the twentieth centuries were able to be rescued and removed from Timbuktu, one of the world’s most important bookselling centers.48 In 2016, the International Criminal Court in The Hague convicted Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi, an Ansar Dine leader, for acts committed in Timbuktu: it is significant as the first ever sentence at an international criminal tribunal for cultural destruction as a war crime.

Iraq and Syria, however, were hit hardest by recent acts of cultural destruction, when the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS, also known as ISIL or Da’esh) propagated a reign of terror from at least 2013 that lasted several years. Nevertheless, the destruction of cultural heritage started much earlier in the region, with illicit excavations generating an illegal trade in ancient artifacts, masterminded from abroad. While this is a tradition going back decades, parallel to the breakdown of the authority of the state in Iraq and Syria, the plunder of archaeological sites has become ever more professional and has currently reached virtually industrial proportions.

ISIS’s terroristic tactics and governance inaugurated a particularly dark age for the cultural heritage of the Middle East, with hate crimes against culture accompanied by egregious human rights violations. Most prominently, the persecution of the Yezidis, nothing short of ethnic cleansing and genocide, was coupled with the annihilation of their cultural heritage.49 In addition, the images of the destruction at the museums in Mosul, Nineveh, Nimrud, Hatra, and particularly the devastation to the Roman ruins of Palmyra (fig. 3.4), accompanied by the savage murder of the site’s chief archaeologist, Khaled al-Asaad, have not been forgotten. The documentation of demolitions of important ancient monuments by ISIS and the global online dissemination of the pictures have turned these infamous acts into special cases of a performance-based, quasi-religious iconoclasm.50

Figure 3.4

Figure 3.4The devastation by ISIS resulted, on the one hand, in the physical loss of important archaeological, historical, cultural, and religious places and objects, and on the other deprived entire communities of their cultural and religious modes of expression and identity. Oppression or destruction of cultural identities and religious communities are nowadays more seldom perpetrated by state actors, but with increasing frequency by nonstate armed groups such as ISIS.51 The group was not only instrumental in demolishing ancient works of art and monuments, it also systematically pillaged and plundered sites and channeled their treasures to the global illegal markets for antiquities and used the proceeds to finance their activities.

The conflicts of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries that have seen the intentional destruction of cultural heritage (such as in the aforementioned Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria) are side effects of a growing form of armed conflict: internal disputes and civil wars. The number of these conflicts has visibly increased since the last decade of the twentieth century, while the number of interstate wars has notably decreased. In the unfolding of these internal conflicts, cultural heritage is involved for two reasons. First, such disputes are deep manifestations of the identities of rival ethnic or religious groups, which turns representations of the cultural heritage of a group into an important and preferred target. This can result in the intentional destruction of cultural artifacts that is rarely required purely for military advantage. And second, conflicts that involve nonstate actors are generally perpetuated by so-called shadow or war economies, and include the plunder of archaeological sites and other cultural monuments, and the illegal sale and resale of artifacts discovered and forcibly torn from their respective historical context.52

Final Thoughts

A review of the long history of the destruction of cultural heritage and a search for links with mass atrocities, including genocide, reveals clear distinctions over time. In ancient times, wars were typically accompanied by the intentional destruction of cultural heritage, and by massacres and enslavement. In late antiquity, cultural artifacts as well as people could become targets in disputes between emerging Christianity and resident pagan cults, for example. However, at the core of such strife was the redistribution of political and economic power.

This holds true for Byzantine iconoclasm. Although justified theologically, the state pursued political and economic objectives in the conflict, intent on breaking the power of the churches, and particularly the monasteries. The iconoclasm of the Reformation, including preludes throughout the fifteenth century, led to a comprehensive obliteration, and in part also a sell-off, of works of Catholic art in territories under Protestant rule, where art production also plummeted and where artists were often forced to work for patrons outside the Church. Works or arts were damaged, mutilated, “executed,” or ridiculed in mock trials, but not their originators or owners—this difference is significant.

The French and Russian Revolutions that flank the long nineteenth century both initially targeted elites and other representatives of their deposed systems as well as works of art and cultural artifacts that were perceived as a reflection of them. In Russia, the destructive frenzy could be reined in faster than in France, where such vandalism had devasting consequences. Yet through nationalization, France did arrive at a novel understanding of its cultural heritage, while during the early Stalin years in the Soviet Union, art was treated as a commodity, resulting in an unparalleled sell-off. Both revolutions represent profound turning points in the history of their countries, creating countless victims and resulting in massive destruction and loss of cultural artifacts.

The European colonial conquests propelled new ruthlessness into the destruction of cultural heritage. The annihilation of the Aztec and Inca Empires by Spanish conquistadores was also a cultural genocide paralleling the violent reduction of the Indigenous population, either perpetrated directly or occurring indirectly due to the devastating effect of imported diseases. This indeed was a cultural genocide. Events in China and Africa also demonstrate how the destruction of cultural heritage was often accompanied by massacres among the population and that, although the 1899 Hague Convention was in force in Europe, it was willfully not applied elsewhere.

The crimes of National Socialism, whether against the Jewish population of Europe or in the occupied territories of Poland and the Soviet Union, reached a new dimension in the extermination of cultural artifacts and their originators and carriers, wherein the holocaust remains unparalleled: systematically orchestrated physical genocide was accompanied by cultural genocide. In the 1970s, we find a somewhat similar reign of terror by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia that resulted not only in the demolition of countless cultural artifacts but also in the deaths of over one million people. The Nazis and the Khmer Rouge shared, among other traits, the desire to engage in genocide and in the destruction of cultural artifacts, but they also both sold works of art on a grand scale abroad to obtain foreign currency.

Since the 1990s, the intentional destruction of cultural heritage and the pillage and plunder of cultural locales have increasingly become ancillary effects of new types of conflict,53 whether civil wars as in the Balkans, or involving mainly terrorist groups as in the Middle East. They are characterized by their concern for nationality, identity, and group membership, defined ethnically, socially, religiously, politically, territorially, and even linguistically. In this context, as in others, cultural artifacts are an enormously important symbolic resource that strengthens the feeling of belonging and cohesion of a community, and provides a united symbolic repertoire that simultaneously distinguishes a given group from others. Cultural artifacts can, with the aid of memory, ritual, and mythos, establish or revive continuity with past generations.

The goal of such conflicts, fought largely between nonstate armed groups, is often the destruction of a shared history and collective memory that can be accomplished through ethnic cleansing and genocide. These events are particularly likely to occur in weak, failed, or disintegrating states that are no longer actors in their own right but have been subverted and ultimately co-opted by criminal or terrorist groups.54 These conflicts, which have substantially increased in number throughout recent decades, have become considerably more perilous for cultural heritage than the classic interstate wars of the past. When an armed group in these recent conflicts has attempted to exterminate a particular community this has usually been accompanied by cultural heritage destruction. Due to the communication options available today, such an act also tends to play out in front of a global audience, often self-consciously from the perspective of the armed groups uploading media. Perhaps this is the most fundamental distinction relative to earlier times.

Looking back at this long history of intentional destruction of cultural heritage, we find continuities as well as differences. First, the examples clearly demonstrate that despite differing motivations, which may have been political, ideological, or religious, from antiquity to the present, economic factors are also always present, from the redistribution of temple and church treasures of the past to the almost industrial scale of illegal archaeology and illicit trafficking of antiquities today. Second, there is a combination of physical and cultural genocide, especially in modern times but which started in the early colonial era with the Conquista in the New World. It reached a historically unique dimension in the Nazi period, but became a regular companion of the ethnic conflicts and terrorist activities of the later twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

And third, there is a growing consciousness of the need for cultural protection, beginning during the Reformation, when Protestant states attempted to avoid the uncontrolled loss of precious objects that often accompanies anarchic conditions, and taking an important shift in the course of the French Revolution with the development of a new understanding of cultural heritage and the creation of museums as new institutions for its preservation. Today we follow the impulse to protect and to preserve by passing laws at the national and international levels, by declaring intentional destruction of cultural heritage as a war crime or crime against humanity, and even by debating the use of military action to protect. However, if we are not able to develop sharper and more effective means of protection, such destruction will merely continue.

Biography

- Hermann ParzingerHermann Parzinger was appointed director in 1990 and president in 2003 of the German Archaeological Institute, where he headed archaeological excavations in the Near East and Central Asia. Since 2008 he has been president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, one of the largest cultural institutions in the world. For his academic work he has received awards and memberships from academies in Russia, China, Spain, Great Britain, the United States, and Germany. He is the author of fifteen books and over 250 essays on research and cultural policy issues.

Suggested Readings

- Stacy Boldrick, Leslie Brubaker, and Richard Clay, eds., Striking Images, Iconoclasms Past and Present (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2013).

- Noah Charney, ed., Art Crime: Terrorists, Tomb Raiders, Forgers and Thieves (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

- Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution (London: Reaction Books, 1997).

- Joris D. Kila and Marc Balcells, eds., Cultural Property Crime: An Overview and Analysis of Contemporary Perspectives and Trends (Leiden: Brill, 2015).

- Kristine Kolrud and Marina Prusac, eds., Iconoclasm from Antiquity to Modernity (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2014).

- James Noyes, The Politics of Iconoclasm: Religion, Violence and the Culture of Image-Breaking in Christianity and Islam (London: I. B. Tauris, 2016).

- Hermann Parzinger, Verdammt und vernichtet: Kulturzerstörungen vom Alten Orient bis zur Gegenwart (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2021).

- Jo Tollebeek and Eline van Assche, eds., Ravaged: Art and Culture in Times of Conflict (Leuven: Mercatorfonds, 2014).

Notes

Hermann Parzinger, Verdammt und vernichtet: Kulturzerstörungen vom Alten Orient bis zur Gegenwart (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2021). ↩︎

Alexander Demandt, Vandalismus: Gewalt gegen Kultur (Berlin: Siedler, 1997), 272; and Nigel Bagnall, Rom und Karthago: Der Kampf ums Mittelmeer (Berlin: Siedler, 1995). ↩︎

Sabine Holz, “Das Kunstwerk als Beute: Raub, Re-Inszenierung und Restitution in der römischen Antike,” in Der Sturm der Bilder: Zerstörte und zerstörende Kunst von der Antike bis in die Gegenwart, ed. Uwe Fleckner, Maike Steinkamp, and Hendrik Ziegler (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2011), 35–43. ↩︎

Stefan Maul, “Zerschlagene Denkmäler: Die Zerstörung von Kulturschätzen im eroberten Zweistromland im Altertum und in der Gegenwart,” Bildersturm (Winter 2006): 163–76. ↩︎

Johannes Hahn, “The Conversion of Cult Statues: The Destruction of the Serapeum 392 A.D. and the Transformation of Alexandria into the ‘Christ-Loving’ City,” in From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity, ed. Johnnes Hahn, Stephen Emmel, and Ullrich Gotter (Leiden: Brill, 2008), 335–65. ↩︎

Tom M. Kristensen, “Religious Conflict in Late Antique Alexandria: Christian Responses to ‘Pagan’ Statues in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries CE,” in Alexandria: A Cultural and Religious Melting Pot, ed. George Hinge and Jens A. Krasilnikoff (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2009), 158–75. ↩︎

Charles Barber, Figure and Likeness: On the Limits of Representation in Byzantine Iconoclasm (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002). ↩︎

Horst Bredekamp, Kunst als Medium sozialer Konflikte: Bilderkämpfe von der Spätantike bis zur Hussitenrevolution (Frankfurt: Edition Suhrkamp, 1975), 166–76. ↩︎

Franz Machilek, ed., Die hussitische Revolution: Religiöse, politische und regionale Aspekte (Cologne: Böhlau, 2012). ↩︎

Bob Scribner, ed., Bilder und Bildersturm im Spätmittelalter und in der Frühen Neuzeit (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1990). ↩︎

Sergiusz Michalski, “Die Ausbreitung des reformatorischen Bildersturms 1521–1537,” in Bildersturm: Wahnsinn oder Gottes Wille? ed. Cécile Dupeux (Zurich: NZZ-Verlag, 2000), 46–51. ↩︎

Martin Warnke, “Ansichten über Bilderstürmer: Zur Wertbestimmung des Bildersturms in der Neuzeit,” in Bilder und Bildersturm im Spätmittelalter, ed. Scribner, 299–305. ↩︎

Sergiusz Michalski, “Das Phänomen Bildersturm: Versuch einer Übersicht,” in Bilder und Bildersturm im Spätmittelalter, ed. Scribner, 69–124. ↩︎

Jürgen Kocka, Das lange 19. Jahrhundert: Arbeit, Nation und bürgerliche Gesellschaft (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 2002); and Jürgen Osterhammel, Die Verwandlung der Welt: Eine Geschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts (Munich: C. H. Beck 2009). ↩︎

Simone Bernard-Griffiths, ed., Révolution française et vandalisme révolutionnaire (Paris: Universitas, 1994). ↩︎

Richard Clay, Iconoclasm in Revolutionary Paris: The Transformation of Signs (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2012), 39–48. ↩︎

Christine Tauber, Bilderstürme der Französischen Revolution: Die Vandalismusberichte des Abbé Grégoire (Freiburg: Rombach, 2009). ↩︎

Paul Wescher, Kunstraub unter Napoleon (Berlin: Gebrüder Mann, 1976), 33. ↩︎

Stanley Idzerda, “Iconoclasm during the French Revolution,” American Historical Review 60 (1954): 13–26. ↩︎

John H. Elliot, “The Spanish Conquest and Settlement of America,” in The Cambridge History of Latin America, ed. Leslie Bethell, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 149–206. ↩︎

Bernard Brizay, Le sac du Palais d’Été: L’Expédition anglo-française de Chine en 1860 (Monaco: Du Rocher, 2003). ↩︎

Diana Preston, Rebellion in Peking: Die Geschichte des Boxeraufstands (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2001). ↩︎

Leonhard Harding, Das Königreich Benin: Geschichte—Kultur—Wirtschaft (Oldenburg: Walter de Gruyter, 2010). ↩︎

Jost Dülffer, Regeln gegen den Krieg? Die Haager Friedenskonferenzen von 1899 und 1907 in der internationalen Politik (Vienna: Ullstein, 1981). ↩︎

Thomas Klein, “Die Hunnenrede (1900),” in Kein Platz an der Sonne: Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, ed. Jürgen Zimmerer (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2013), 164–76. ↩︎

Mark Derez, “The Burning of Leuven,” in Ravaged: Art and Culture in Times of Conflict, ed. Jo Tollebeek and Eline van Assche (Leuven: Mercatorfonds, 2014), 81–85. ↩︎

Derez, Ravaged, 84. ↩︎

Natalya Semyonova and Nicolas V. Iljine, eds., Selling Russia’s Treasures: The Soviet Trade in Nationalized Art (New York: Abraham Foundation, 2013), 14. ↩︎

Semyonova and Iljine, Selling Russia’s Treasures. ↩︎

Semyonova and Iljine, Selling Russia’s Treasures, 17. ↩︎

Peter Adam, Kunst im Dritten Reich (Hamburg: Rogner & Bernhard, 1992). ↩︎

Peter-Klaus Schuster, ed., Die “Kunststadt” München 1937: Nationalsozialismus und “Entartete Kunst” (Munich: Prestel, 1998). ↩︎

Thomas Kellein, ed., 1937: Perfektion und Zerstörung (Bielefeld, Germany: Ernst Wasmuth Verlag, 2007). ↩︎

Stefan Koldehoff, Die Bilder sind unter uns: Das Geschäft mit der NS-Raubkunst und der Fall Gurlitt (Berlin: Verlag Galiani, 2014). ↩︎

Martin Friedenberger, Fiskalische Ausplünderung: Die Berliner Steuer- und Finanzverwaltung und die jüdische Bevölkerung 1933–1945 (Berlin: Metropol-Verlag, 2008). ↩︎

Ulrike Hartung, Raubzüge in der Sowjetunion: Das Sonderkommando Künsberg 1941–1943 (Bremen: Edition Temmen, 1997). ↩︎

Guobin Yang, The Red Guard Generation and Political Activism in China (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016). ↩︎

Martin Slobodník, “Destruction and Revival: The Fate of the Tibetan Buddhist Monastery Labrang in the People’s Republic of China,” Religion, State and Society 32, no. 1 (2004): 7–19. ↩︎

Tess Davis and Simon Mackenzie, “Crime and Conflict: Temple Looting in Cambodia,” Cultural Property Crime: An Overview and Analysis of Contemporary Perspectives and Trends, ed. Joris D. Kila and Marc Balcells (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 292–306. ↩︎

András J. Riedlmayer, Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Bosnia-Hercegovina, 1992–1996: A Post-war Survey of Selected Municipalities (Cambridge: Fine Arts Library, 2002). ↩︎

Michelle Defreese, “Kosovo: Cultural Heritage in Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Archaeology 5, no. 1 (2009): 257–69. ↩︎

Finbarr B. Flood, “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum,” Art Bulletin 84, no. 2 (2002): 641–59. ↩︎

James Noyes, The Politics of Iconoclasm: Religion, Violence and the Culture of Image-Breaking in Christianity and Islam (London: I. B. Tauris, 2016), 60–69. ↩︎

Jamal J. Elias, “The Taliban, Bamiyan, and Revisionist Iconoclasm,” in Striking Images, Iconoclasm Past and Present, ed. Stacy Boldrick, Leslie Brubaker, and Richard Clay (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2013), 145–63. ↩︎

Finbarr B. Flood, “Religion and Iconoclasm: Idol-Breaking as Image-Making in the ‘Islamic State,’” Religion and Society 7 (2016): 116–38. ↩︎

Hermann Parzinger, “Götterdämmerung in Pakistan,” in Schliemanns Erben: Von den Herrschern der Hethiter zu den Königen der Khmer, ed. Gisela Graichen (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany: Gustav Lübbe Verlag, 2001), 132–91. ↩︎

Elias, “Taliban, Bamiyan, and Revisionist Iconoclasm,” 157; and Sabine von Schorlemer, Kulturgutzerstörung: Die Auslöschung von Kulturerbe in Krisenländern als Herausforderung für die Vereinten Nationen (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2016), 842. ↩︎

Dmitry Bondarev and Eva Brozowsky, Rettung der Manuskripte aus Timbuktu (Hamburg: University of Hamburg Press, 2014), 7–18. ↩︎

Von Schorlemer, Kulturgutzerstörung, 76. ↩︎

Flood, “Religion and Iconoclasm,” 120; and Horst Bredekamp, Das Beispiel Palmyra (Cologne: Walther König, 2016), 14–17. ↩︎

Von Schorlemer, Kulturgutzerstörung, 100; and Joris D. Kila, “Inactive, Reactive, or Pro-active? Cultural Property Crimes in the Context of Contemporary Armed Conflicts,” Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 1, no. 4 (2013): 319–42. ↩︎

Sigrid van der Auwera, “Contemporary Conflict, Nationalism, and the Destruction of Cultural Property during Armed Conflict: A Theoretical Framework,” Journal of Conflict Archaeology 7, no. 1 (2012): 49–65. ↩︎

Mary Kaldor, New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999); and Parzinger, Verdammt und vernichtet, 287–90. ↩︎

Van der Auwera, “Contemporary Conflict, Nationalism, and the Destruction,” 61. ↩︎